It wouldn’t be going too far to say 90% of my wardrobe is made up of merch shirts. While I obviously have my corporate wear for the days I go into the office, or for when I’m presenting at conferences or workshops, my usual WFH and weekend wear includes a t-shirt repping a band, sports team, or athlete.

This morning, for example, I grabbed my Oscar Piastri 2024 McLaren home race shirt to wear as I made my way through my Friday to-do list. But a few hours later, I saw myself in the mirror and a horrible thought briefly entered my mind: “oh…but this is outdated”.

…What?

You see, Oscar recently released his 2025 home race collection and after seeing it all over my social media feeds, a sense of FOMO had seeped into my subconscious.

Would the Average Joe seeing me in a Teams meeting or at a cafe wearing my shirt care that it was from last year? Obviously not. And it will fit right in when I wear it to the Melbourne Grand Prix in a couple of weeks! But the part of me who seen how his fandom has been discussing the merch on social media in recent weeks still felt like I was behind the times because I hadn’t dropped a few hundred dollars on the newest collection.

How did we get here?

It wasn’t too long ago that the status in merchandise came from something being proof that you were there. Like, oh my gosh, you have a shirt from Harry’s first solo tour1, or from the year the Caps won the cup2, or that super special edition that was only around for a season. Fans would proudly wear the merch for years, in part to signal their fannish history to others and in part to help themselves relive key moments of their fandom journey. While there’s always been debate around whether you should wear a band’s shirt to their gig, and gatekeeping around how much of a fan you need to be to wear merch is a tale as old (and frustrating) as time, the historic roots of merchandise are ultimately in memory and longevity, not disposability.

However, we’ve seen a shift in recent years in many fandoms to a “merch drop” culture.

Rewarding consumption

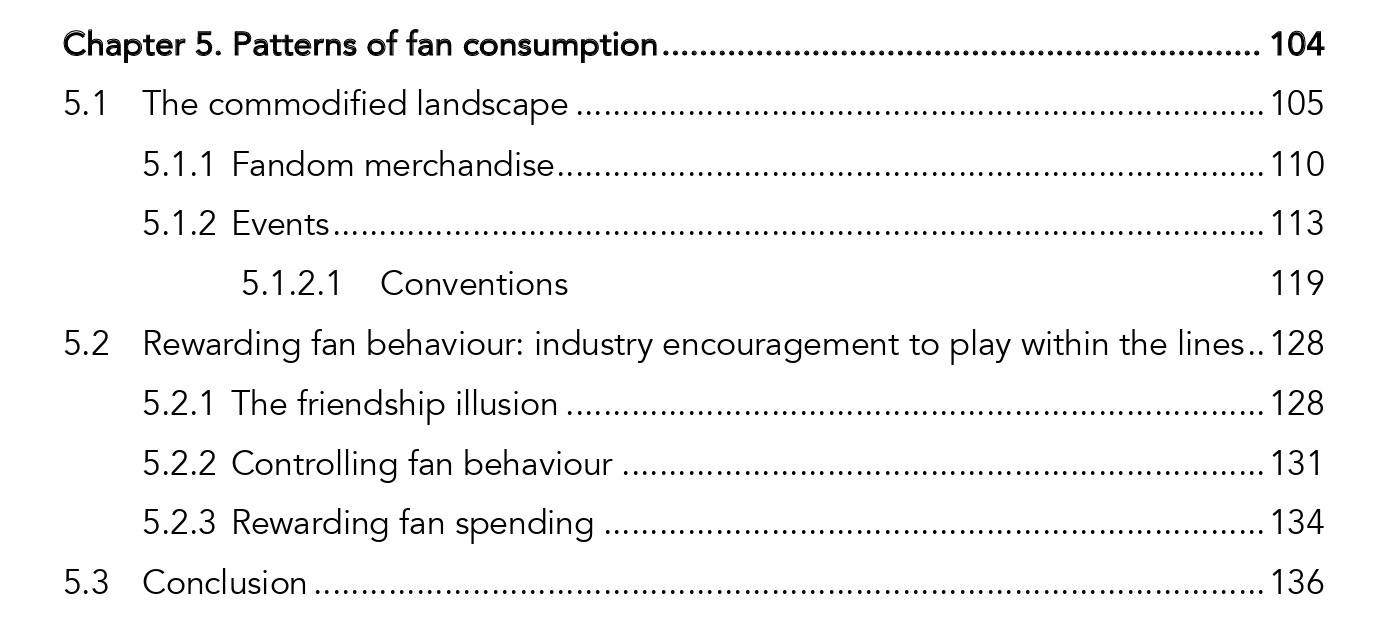

A large part of my PhD thesis explored fan consumption. Its title was even “Oh my god, how did I spend all of that money: Lived experiences in two commodified fandom communities”! So, I’ve spent a lot of time researching, writing, and thinking about how and why fans consume.

Much of the merch drop culture we now see works hand in hand with a fan engagement strategy where fans are rewarded with attention.

For a lot of fans, fandom participation is built around a desire to engage with their favourite celebrity. It doesn’t matter if this celebrity is a singer, actor, athlete, or influencer, the underlying motivation remains the same: they want to be noticed.

The Economy of Attention (not to be confused with the Attention Economy) is a helpful theory that allows us to understand this. The Economy of Attention describes the concept of “attention capital”, or the value of receiving attention rather than giving it. As Georg Franck outlines,

What is important, then, is not only how much attention one receives from how many people, but also from whom one receives it – or more precisely, with whom one is seen. The reflections of somebody’s attentive wealth thus becomes a source of income for oneself. Mere proximity to celebrity makes a little celebrity3.

So, fans want the status that comes from getting a celebrity’s attention (no matter how fleeting that attention may be). But what then becomes important for us when thinking about merchandise is a second element of attention capital: it has a trickle-down effect. So, if you can’t get attention from The Celebrity, you want attention from those who are in their orbit. Which, in many cases, is their marketing team through the guise of fan club social media account. These accounts exist as proxies for celebrities, providing access and information alongside the allure of being in their inner-circle. They have what fans so desperately want for themselves.

Taylor Swift is the master of this strategy through her Taylor Nation accounts. Her fans understand Taylor Nation hold the keys to any and all access to Taylor, and are desperate to get their attention. After all, you can’t be noticed by Taylor until you’re noticed by her team. One of the main ways to get their attention? Screenshotting your merchandise receipt and sending it to them on social media.

Others have written about the murky waters Taylor Swift walks through when it comes to fast fashion, both in terms of her merchandise and the themed outfits fans wear to her shows. Taylor’s merchandise output has increased exponentially since 2020. While some fans are asking whether it’s necessary, you just need to scroll social media after a new drop is announced to see that there are more than enough still ready to buy, buy, buy. There’s even a discord bot that provides updates from the backend of her store so that fans can be notified as soon as things are added!

The kind of merchandise collecting we see in these situations isn’t exactly new - fans have been collectors for as long as there have been things to collect. But we have to ask ourselves if we’re crossing a line from truly exclusive and memorable pieces of merchandise to add to high-quality collections to…just buying things to share for social media likes.

And yes, I am well aware that our world is on fire and sometimes we do just need to purchase things that bring joy into our lives. I can’t talk - I spend close to $20 a day on treats from my favourite cafe4! I’m not judging any single individual for their habits, but I’m questioning the industry as a whole. After all, this kind of strategy isn’t just problematic when thinking about sustainability; it also leaves behind fans who can’t keep shelling out endless amounts of money for merchandise, for whatever reason.

It’s not just Taylor Swift playing the “rewarding you for consumption” game - we have also seen this strategy expand across celebrity fandoms. I’ve been paying particular attention to how it plays out in the Formula 1 driver space, where Lando Norris’s LN4 team almost carbon-copies the Taylor Nation strategy. Their extremely-frequent merchandise drops quickly sell out…but does that mean they need to keep releasing them? What is it actually giving to fans?

What are our options?

There’s a lot we can learn from sustainable fashion activists like Aja Barber, who discuss the fashion industry and issues within it more broadly. But when it comes to merchandise, we do also need to apply a fan theory lens to better understand how we can sustain fan engagement and connection without adding more and more clothing waste to the world without a longer-term strategy in place.

Matt Hymers from Connected Fanatics spends a lot of his time talking about sustainability with a specific focus on the merchandise space. Connected Fanatics have a fascinating product, where technology is embedded into a piece of clothing to unlock experiences and encourage connection. Re-wearing the merch across years allows you to add to the experiences, stored memory, and community, creating a reason to say no to the continual drops of the newest thing. It’s new enough that we don’t yet have any significant evidence for its impact…but I’m hopeful that it’s a step in the right direction that shows fans that we do have other options.

At the end of the day, I think it all stems down to asking ourselves a very simple question: do we actually want the new shirt/hat/hoodie/jersey/etc., or do we want the sense of belonging and connection the purchase momentarily creates?

If fans are seeking engagement and status, how can organisations work to build this in a way that doesn’t simply rely upon endless merch cycles and resharing receipts and package deliveries? If owning the latest merch creates a sense of community, how else can we foster this?

Community isn’t built on owning complete merch collections. While the short-term metrics that come from these strategies are effective…eventually organisations will hit the limit of their fans’ capacity to spend and willingness to continuously be sold to. Fandom is not a transaction, it’s a relationship. And that relationship is there regardless of what year someone’s merch is from, or ultimately, whether they own any merch at all.

Consumption is an inevitable part of modern fandom, but it shouldn’t be seen as the most important part of an organisation’s fan engagement strategy. My support for Oscar isn’t magically lessened because I’m wearing a shirt from 2024, if anything, it shows that I’ve been there for him and I’m staying here for him. And I think that’s a much more sustainable way for all of us to be thinking about our relationship to merch.

This may be a personal example

…this is also a personal example, as anyone who has ever seen me going for a run in my Caps Championship hat can attest to

Georg Franck 2019, ‘The economy of attention’, Journal of Sociology, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 8–19.

In my defence, it’s an expensive cafe! I’m not buying half the shop.

So fascinating! I’ve never heard of the Economy of Attention in terms of receiving rather than giving attention.